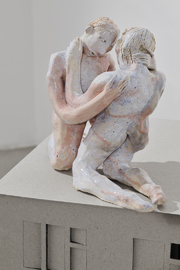

Amoured Concrete, Clemens Sels Museum/ Artothek Cologne Photo: Carsten Gliese/ Mareike Tocha

The Unboxing Experience, the Clemens Sels Museum Neuss invites to Phase 2, Resonating Voices, opening on Thursday, June 26, 2025. For this phase, the curators have asked emerging international artists to engage their works in dialogue with pieces from the museum’s collection. The goal is to expand existing discourses and establish new points of emphasis. These encounters give rise to equal and reciprocal juxtapositions – Resonating Voices. Resonance – in the sense of echo, reflection, contradiction, or continuation – needs space in order to be heard. At its best, the museum itself can become such a resonant space.

“The Unboxing Experience” is curated by Lara Bader and Marlene Kurz, scholarship holders of Residence NRW⁺ 2024/2025. In addition to the project for the Clemens Sels Museum Neuss, the two curators from Germany and Switzerland have been invited to develop and realize an exhibition with the NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein.

Text: Clemens Sels Museum

English Text (press release)

The title of the exhibition plays with the English term for reinforced concrete "armoured concrete" and the French word "l'amour" for love. What is playfully combined in the neologism "Amoured Concrete" often seems incompatible and contradictory in reality: tender emotions and repellent concrete façades of prefabricated buildings. Individual relationships and ever-same modular architecture. Hope and decay. But it is precisely in these tensions that there is much that is utopian, says artist Anna Bochkova. She spent her childhood in an Eastern European "slab" and proves with her multi-layered installation that art has the power to shift dimensions and bring diverging feelings together in surprising new ways.

In the artothek, Bochkova places fragile ceramic figures, which meet in poetic and tender gestures, between prefabricated buildings made of simple grey cardboard. In the context of so-called "social hotspots", she places the longing for love, innocence and a protected togetherness. The figures carry flowers into the spaces between the buildings to sow tenderness and beauty, to plant something there. This touches and shakes up the images and ideas that we associate with prefabricated housing estates, and perhaps also with Eastern Europe.

The installation is a small world that invites you to immerse in it. It plays with contradictions and allusions, uses materials and gestures. Although "hope" is certainly one of the central messages, this hope is born in pain. A pain that Anna Bochkova artistically absorbs and transforms, so that in the end the lightness and simplicity of the aesthetic statement remain in the memory.

Text by Heiko Lietz

A prefabricated building without balconies can be built in five days, with balconies in fourteen. How long does it take for it to become a home? How long does the

feeling of home stay with someone? How quickly does someone have to rush down a staircase to reach the safety of their own four walls?

The exhibition ‘Armoured Concrete’ brings together two groups of works. On the one hand, facades of prefabricated buildings made of cardboard, on the other, figurative ceramic figures of people with

flowers. When Anna Bochkova told me about this project, she began by saying that her upbringing in a prefabricated housing complex in Rostov-on-Don informs much of her work. She told me about how she

had recently been to Belgrade and had felt at home in a similar prefabricated housing estate, and how she and a friend recognised the apartment buildings they had grown up in. A familiar feeling in a

foreign country, coupled with the knowledge that they currently cannot return to these buildings.

Of course, they were not the same houses, but the residential complexes were built in an architecturally similar way and were built in all landscapes of the former Eastern Bloc, regardless of

location. The design of these complexes followed similar principles, the apartments had the same shapes, the same layouts and relationship to each other. The buildings act as sound insulation from

the large streets outside, they form quiet courtyards. Access to these courtyards has to be learned, they are hidden from strangers. The paths within these complexes are aligned, the distances and

paths between residential buildings, schools, bakeries or schools are scientifically measured and planned. From this point of view however, Anna Bochkova's works do not ask about the logic of the

buildings, but about their residents. They refer to the way architecture influences the social constellation, how movements are influenced and learned through it, which anonymous places are created

by it, how architectures and buildings produce harshness, violence, but also calmness and the feeling of home. These idealistic, well-planned residential areas turned into social hot spots after the

collapse of the Soviet Union due to the lack of various forms of infrastructure and due to urban housing and land use policies. While Anna Bochkova was interested in the individual design of the

private apartments that she saw during visits or in the windows of the always identical grey facades as a child, the works shown in Arthotek Cologne deal with the spaces between the buildings, which

also allows their spatial and temporal reference to be expanded. If Anna Bochkova refers to her memories, to areas of tension between individuals and buildings and their temporal change, this also

leads my gaze to residential areas and their development in Germany. Whether in relation to Rostov-on-Don, Belgrade, Kölnberg in Cologne or Gropiusstadt in Berlin, Bochkova's works ask about the

potential of these places. How can loving community environments (armour-ed concrete) emerge from armoured concrete?

The cardboard architecture and figures of Anna Bochkova pose the same question. While poplars are the most popular trees in these building complexes, because they grow the fastest and can produce the

most oxygen, Bochkova's ceramic figures carry flowers into the spaces between the buildings to show tenderness and beauty, to plant something that will stand firm even in the wind. The gesture of

handing over flowers is a gesture of recognition and appreciation that counteracts violence. At the same time, it refers to traditions and forms of protest. Against the background of the current

political situation, the song “Where have all the flowers gone” came to my mind during our conversation. Anna told me that the version of this song known in Germany goes back to the Don Cossack song

Koloda Duda and that her great-grandfather had sung this song to her before she went to sleep. The flowers that disappear due to war, loss, hardship and inhumanity return through the figures in

Bochkova's installation. They refer to the laying of flowers at specific monuments, which, through the affective charge of grief, becomes an expression of political orientations in today's Russia. If

you look at these exemplary, affective reference possibilities of the flower and place it between the cold, reinforced concrete facades, they show themselves as a reference to possible other forms of

development and growth of a diverse coexistence that can develop in the communal liminal places between buldings. A form of development that seeks to unite affects, feelings, steadfastness and

protest, that is born from memories and grows into the future.